Motorsport noise impacts: the Wakefield Park Judgment

The Land & Environment Court of NSW recently handed down a judgement related to the Wakefield Park Raceway near Goulburn, in a case centring around noise impacts.

Motorsport noise impact assessment in NSW is always contentious, with an absence of any state-wide noise policy. This judgement raises a number of issues that will be of interest to acousticians, planners and motorsport operators.

Intro

The judgement related to NSWLEC 1321 (2021/199172) involving BAC WMR Holdings Pty Ltd v Goulburn Mulwaree Council. The full judgement can be found here with Consent Conditions also available at that link.

The case involves a Development Application for ongoing use of the Wakefield Park Raceway near Goulburn, including some building/infrastructure works. Two acoustic experts were involved, being Dr Renzo Tonin for the applicant and Mr Stephen Gauld for the respondent.

There is an absence of specific policy to address noise from motorsport facilities in NSW. The EPA Environmental Noise Control Manual provided some guidance but has since been repealed. The EPA Noise Guide for Local Government notes that regulation of motorsport facilities rests with the local Council and that the Offensive Noise Test may be used. It does provide some further information in a Case Study example, but no explicit criteria. In this context, any precedent from the court may be of interest to those involved with other similar facilities.

The facility was originally granted operating consent in 1993. The Statement of Environmental Effects in 1993 assessed on the basis of "race meetings limited to 4 per month". The facility now hosts a significantly higher number of events per year, and the allowable number of events was central in the case.

Disclosure: Neither I nor Marshall Day Acoustics has been involved in the case. I have not conducted work for BAC WMR Holdings Pty Ltd but have carried out works for Goulburn Mulwaree Council in the past. This article is based solely on a review of the judgment and consent conditions linked above, i.e. I have not seen any further documents, acoustic reports etc related to the matter. Whilst I know Dr Tonin and Mr Gauld I have not discussed the matter with either of them.

What do the outcomes imply for the motorsport industry?

1. The noise compliance burden for reporting, monitoring, staffing etc is likely to increase. Systems needed to ensure compliance with administrative requirements would be likely to be a significant step change for most motorsport facilities.

The Consent Conditions, in this case, require continual noise monitoring and reporting including:

"Static vehicle noise testing must be completed on every vehicle prior to the vehicle entering the circuit."

"The existing Simpson Group Soundweb system (or equivalent) must monitor and record noise levels emitted from any event or activity during all operating hours."

"A compliance report is to be provided by the applicant to Council quarterly (being every 90 days), within 30 days of the end of the previous quarter to demonstrate the extent of compliance throughout the previous 90 days. The report is to be independently verified by a suitably qualified and experienced Noise Consultant and funded by the applicant."

"The applicant is to develop a Continual Improvement Plan. The Continual Improvement Plan is to be submitted to Council annually, within 30 days of the end of the previous calendar year. The plan is to be independently verified by a suitably qualified and experienced Noise Consultant and funded by the Applicant.”

"Council is to be provided with access to view real time and historical data being captured or previously captured by the Soundweb system via a direct system login that is accessible 24 hours per day."

2. A set of conditions similar to this case would require regular and ongoing input from a trusted acoustic engineer, as well as an investment in ongoing noise monitoring equipment. This is likely to be a significant cost item and the management of this relationship and perhaps the tendering process for such works will also be a significant item for consideration.

3. Relationship management with neighbours will remain important. As with any industry, good relations and attentiveness to feedback or complaints from affected parties over years of operation may have a significant effect on the success of any new Development Applications.

The judgment notes resident comments including that:

“There appears to have been a long period of ineffective enforcement, lack of community consultation and even financial support for the Raceway despite a record of disregard for proper planning process” and;

“There is also a common thread in the public submissions at what is considered a lack of regard for the resident community demonstrated by the Applicant in failing to manage social media activity by Raceway participants and supporters seeking to ‘troll’ neighbouring and nearby properties.”

4. Having a receiver supporting the application, or even acquiring a residence, may help an application progress in the short term. However, tenants/residents (and opinions) can change over time and such an arrangement does not guarantee a permanent solution.

A number of residents near the circuit were in support of the proposal and these were not assessed as residential receivers. However, the consent conditions note that:

"It should be noted that agreements reached with landholders should not be regarded as permanent (for example, changes in land tenure) and should be reviewed by the Applicant on at least an annual basis."

5. Many modern commercial motorsport facilities operate on a daily (or close to) basis, with a range of corporate, driver training, ride experience etc events supplementing the less common large race meets. Wakefield Park appeared to have an assumption of 4 days of events per month referenced in the 1993 Statement of Environmental Effects which has now affected its operations 29 years later. Other facility operators may want to check their existing consent conditions and compare to how they now operate.

What can acoustic consultants take from the judgment?

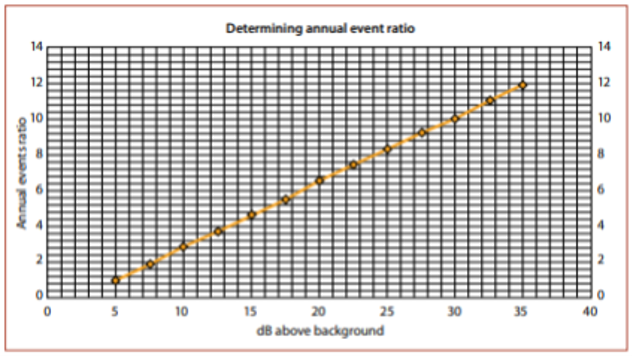

1. That the court gives "considerable weight" to the event multiplier produced by the EPA in the Noise Guide for Local Government, even though this is only included as part of a 'case study' in the Guide.

As noted: "In essence, the experts agree that for every event held at the Raceway that exceeds a reasonable level of noise, provision should also be made for respite from such noise. As it was put by Dr Tonin, the maximum number of events permitted each year is analogous to a ‘bucket of balls’, where the rate at which balls are withdrawn represents the db(A) above background, and the overall number of balls represents the total number of events determined appropriate for the year."

The commissioner noted that "After considering the written and oral evidence of the acoustic experts, I state here that I give considerable weight to the Event multiplier produced by the EPA in the NGLG." And also noted that "the experts agreed that the number of events for the calendar year should be 365."

For reference the event multiplier chart is reproduced on the right:

2. There is now precedent for reference to the NPfI Amenity noise levels for motorsport facilities. The EPA NPfI specifically excludes from the policy its application to "noise from sporting facilities, including motorsport facilities. The judgement is not entirely clear on how the Amenity noise levels were specifically used in this instance.

However, the judgment notes that "Whilst the EPA Noise Policy for Industry specifically excludes assessment of motor sport facilities the experts agreed that the recommended ‘amenity noise levels’ found in Table 2.2 provide a useful benchmark.”

3. Not all forms of motorsport are equal and the character of the noise may be an important factor, not just the noise level.

Drag racing is often treated differently from other forms of motorsport, due to vehicle noise levels being commonly above the CAMS limits applied to other classes. In this case, "Drifting" events are also specifically excluded, possibly related to noise character, rather than noise level.

A resident comment noted that "Of particular concern is the motor sport known as ‘drifting’ due to the skidding/screeching squeal of rubber that irritates and creates a form of anxiety". A consent condition forbids any drifting activity at the site.

Conclusion

The absence of a state or nation-wide criteria for motorsport facilities makes assessment of such facilities difficult. There exists considerable risk to proponents of new facilities as well as, in the case of Wakefield Park Raceway, facilities with existing approvals. Many motorsport facilities around Australia operate under consent conditions (and supporting reports and assessments) that are many years or decades old. In some cases, operators may not be aware of, or be complying with the conditions and assumptions contained in those approvals. It is through that lens that operators should consider their position and take steps to ensure their ongoing licence to operate.

For the acoustic consultant, the judgment offers a number of interesting technical takeaways, including the weight given to the NGLG Case Study event multiplier approach and the applicability of the NPfI Amenity noise levels as a benchmarking tool for motorsport facilities. However, it also raises questions as to the character of different types of motorsport noise and what effect that character may have on acceptability at a venue.